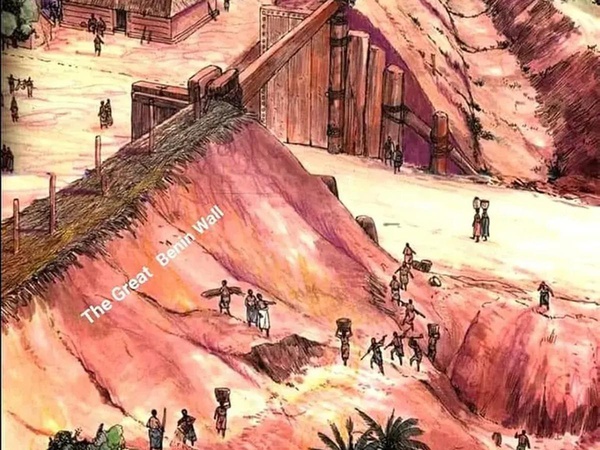

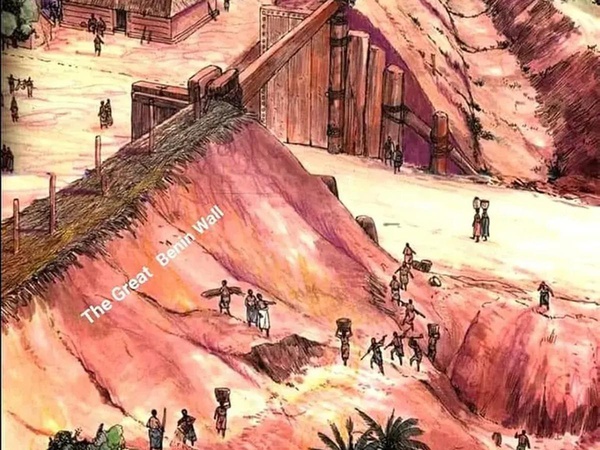

<p>In the heart of what is now southern Nigeria, the Benin Kingdom (not to be confused with the modern Republic of Benin) flourished for centuries. From around 800 AD until its fall to a British punitive expedition in 1897, it was one of the most advanced and organized states in Africa. Its capital, Edo (now Benin City), was described by early European visitors in the 15th and 16th centuries as a metropolis of astonishing scale and order. Portuguese explorers wrote of a city wider than Lisbon, with broad, straight streets, specialized quarters for craftsmen, and a magnificent royal palace. What protected and defined this urban civilization was not just its social structure, but a monumental physical barrier the Great Wall of Benin, also known as the Benin Earthworks.</p><p><img alt="" src="/media/inline_insight_image/1000286696.jpg"/></p><p>This was not a single wall, but a vast, interconnected network of moats and ramparts. The people of Benin dug a staggering series of ditches, piling the earth inward to create formidable embankments. It functioned as a fortified city wall, a territorial boundary, and a system of demarcation for farmland and villages. The wall was built not only to defend the kingdom from invaders but also to mark territories, organize communities, and regulate movement within the city. Each district had its own local leaders, who answered to the Oba, the king, creating a highly organized system of governance. In this way, the wall was both a physical and symbolic representation of the Oba’s authority and the kingdom’s unity.</p><p><br/></p><p>The scale of the Great Wall of Benin is almost incomprehensible. Estimates from satellite imagery and archaeological surveys suggest the interconnected earthworks spanned over 16,000 kilometers, or nearly 10,000 miles. For comparison, China’s Great Wall stretches about 21,196 kilometers (13,171 miles), making the Benin Wall the longest archaeological earthwork ever constructed. It is estimated that building it required roughly 100 million hours of labor, spread over generations. Construction began around 800 AD and continued intermittently until the mid-15th century. The Edo people dug deep moats, sometimes reaching 20 meters, and piled the earth inward to form embankments. Terracing was used in certain areas to strengthen defenses and manage rainwater, showing a sophisticated understanding of both engineering and the natural landscape.</p><p><img alt="" src="/media/inline_insight_image/1000286695.jpg"/></p><p>Beyond its defensive and administrative functions, the Great Wall of Benin had immense cultural and social significance. It unified the kingdom physically and symbolically, connecting villages, farmland, and urban quarters. It delineated sacred spaces and ceremonial routes, integrated marketplaces, and helped maintain social order. The wall reflected the priorities of the Edo people security, organization, and cultural cohesion. Portuguese explorers who visited Edo in the 15th century were amazed by the city’s scale and order, noting the impressive fortifications and organized districts.</p><p><br/></p><p>Fragments of the wall remain today across Benin City, a haunting reminder of the ingenuity, ambition, and organizational skill of the Edo people. The Great Wall of Benin challenges us to rethink history not as a linear story written by conquerors, but as a tapestry of innovation, culture, and human determination. Remembering the wall is an act of reclaiming pride, knowledge, and identity, and it reminds us that the brilliance of the past still shapes the possibilities of the future.</p><p><br/></p><p>If this was possible centuries ago, what could we build today if we remembered and honored the ingenuity of our ancestors?</p><p><br/></p><p>PS: It’s kind of hard for me to stay on the surface without diving deep, but I tried my best to shorten it and make it easier to read. I just had to share this for now, and with time, I might bring up more stories and discoveries.</p>

Comments